By Andrew Nagorski

On Sept. 9, 1943, a four-engine British Halifax bomber dropped three Polish paratroopers into their occupied homeland. One of them was Elżbieta Zawacka, also known as Zo, the sole female member of an elite unit dubbed the Silent Unseen. According to Zo, when the commander of the local resistance group awaiting the drop rushed forward and threw his arms around her, he abruptly leapt back and exclaimed, “A woman!” “No,” she replied, “just an ordinary soldier.”

Zo was anything but ordinary, perhaps the most extraordinary individual among a multitude of larger-than-life figures who routinely took enormous risks to free their country from Hitler’s overlords. Her life encapsulated Poland’s mostly tragic history in the last century, not only during World War II but also under Soviet domination in the postwar era until the country regained its freedom thanks to the Solidarity movement’s victory in 1989. Zo, who died just shy of her 100th birthday in 2009, exemplified every stage of that dizzying journey.

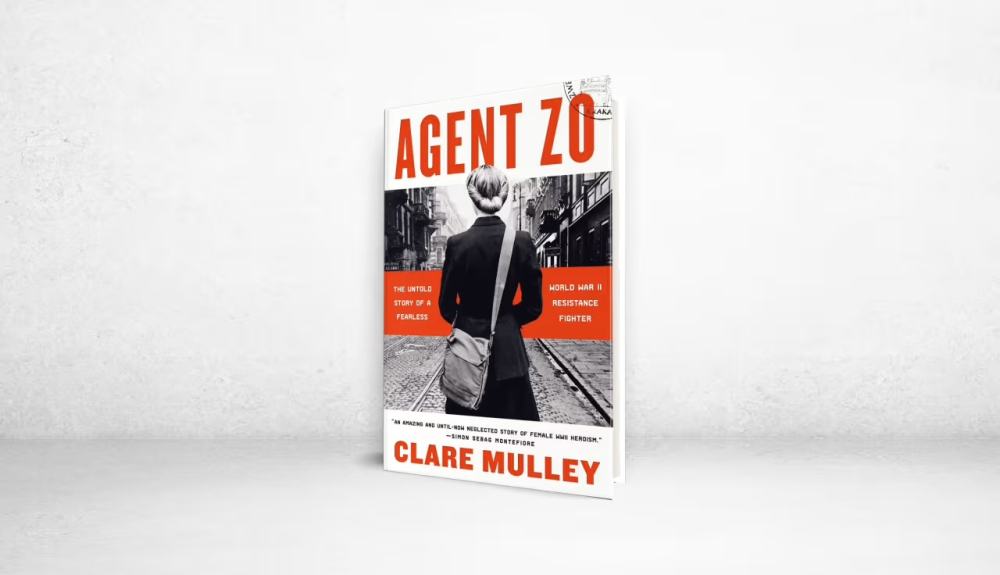

In “Agent Zo,” the British historian Clare Mulley skillfully weaves together Zawacka’s personal story with the broad sweep of events. Ms. Mulley’s previous books include “The Spy Who Loved” (2012), a biography of Christine Granville, the adopted name of a Polish woman who worked for Britain’s Special Operations Executive, the unit charged with subversion and sabotage in occupied Europe. The author’s fascination with the role of women in wartime intrigue is both infectious and mesmerizing.

In the late 18th century, Poland was partitioned out of existence by its neighbors—Prussia, Russia and Austria. Toruń, the city where Zo was born, was in Prussian-annexed territory, and she and her siblings grew up speaking German, since Polish was officially banned. But they all knew they were Polish. As Ms. Mulley puts it: “Learning to lead a double life, with secret layers of identity, concealment came to them naturally.” After World War I, Poland reappeared on the map as an independent state, with Toruń inside its new borders. It was then that Zo learned to speak Polish, but she had always considered herself a fervent patriot.

Zo studied mathematics at Poznań University, putting her on the trajectory of a distinguished teaching career. She also joined the Women’s Military Training association. By 1937 she qualified as a senior instructor and was appointed commander of the Silesian region. Women were still considered to be auxiliaries, assigned to supporting roles for the men who would engage in actual combat. But as another global conflict loomed, Zo saw herself and her charges differently. “We were young and hungry for action,” she said. “We didn’t consider ourselves inferior to men, and we wanted to prove it. We wanted to serve Poland.”

The German invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, coupled with the Soviet invasion from the east that followed 16 days later, meant that Polish forces were quickly overwhelmed, and their country was carved up by Hitler and Stalin. But defeat did not produce surrender. Many Polish soldiers who escaped captivity, including my father, regrouped in France and then Britain. Others who stayed joined the Home Army, which grew into the largest resistance organization in occupied Europe. It numbered about 400,000 men and 40,000 women.

In November 1939, Zo swore her allegiance to the resistance and quickly developed a network of spies in Silesia. She gathered information about German troop deployments, mass executions, arrests and the roundups of Jews into ghettos in preparation for the Holocaust. “Liaison women” had to slip through various occupation zones and checkpoints to make sure that such critical intelligence reached their superiors in Warsaw—and then could be relayed to London, the seat of the Polish government-in-exile.

Given her fluent German, combined with the array of disguises and forged identity papers churned out by the Home Army’s experts, Zo was ideally suited for this role. She repeatedly crossed borders across the Continent, delivering “mail” and money that were essential to maintaining resistance operations. As one friend wrote, she rushed between Warsaw and Berlin “like a whirlwind.” She also made an arduous, two-month journey to London via Spain, nearly dying while crossing the Pyrenees.

In London, she complained about what she saw as the lack of urgency of her superior officers in dealing with the Home Army’s flood of intelligence, and she spelled out what needed to be done to better support those behind enemy lines. It was there, too, that she joined the Silent Unseen, determined to return to Poland to participate in the final stages of the struggle, culminating in the Warsaw Uprising that was launched in August 1944.

During two months of ferocious fighting, she coordinated supply deliveries and care for the wounded while constantly exposing herself to danger. Yet while Hitler gave the order that Warsaw should be “leveled to the ground,” Zo called the first days of the uprising “the most wonderful time of my life.” Fighting to rid their country of the Germans, the Poles also wanted to pre-empt a Soviet takeover, which Stalin fully understood. The Red Army was already nearby but refused to come to their aid.

Hitler made good on his promise to level Warsaw and crush the uprising. Once the Red Army resumed its offensive, Stalin imposed a puppet government. After the defeat of Hitler, Zo took a variety of teaching jobs, but she refused to join the Communist Party and found herself subjected to new persecution, including arrest, torture and imprisonment from 1951 to 1955. The Communist authorities viewed those who had served the Home Army and the government-in-exile as suspect because of their devotion to a free Poland.

Zo was always ready to die for such a Poland. She worked to “preserve from oblivion” the story of the wartime resistance and became an avid supporter of Solidarity. Mercifully, she lived long enough to participate in her country’s rebirth.

Mr. Nagorski is the author of eight books, including “Saving Freud,” “The Nazi Hunters” and “Hitlerland.”