As Russia prepared for its lavish commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II earlier this month, there were predictable calls for the rehabilitation of Joseph Stalin. After all, the Orel city legislature pointed out in its bid to put up monuments to the Soviet leader, he had led the country to victory over Nazi Germany. But the provincial lawmakers didn't stop there. They argued that it's never been proved that Stalin was responsible for the millions of people who were murdered either by firing squads or in the Gulag during his rule.

The fact that many Russians are still in denial about the monstrosity of Stalin's crimes--and that much of the world dismisses their behavior in a way that it would never shrug off Holocaust deniers--is one good reason to welcome the cascade of new books about the Soviet dictator. As Donald Rayfield points out in "Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him" (541 pages. Random House) , a thorough examination of the terror apparatus headed by the secret police, Stalinism remains "a deep-seated infection in Russia's body politic." He adds that Vladimir Putin's regime "does not so much deny as set aside Stalin's holocaust, by celebrating Stalin instead as the architect of victory [in World War II] and the KGB as Russia's samurai."

But that is not the only reason for Stalin's current literary popularity. Theglasnost era of the late 1980s triggered an outpouring of documents, personal recollections and histories of the Stalinist era that spilled over into much of the 1990s. Western authors are tapping into that pool of new information--even as they are discovering that, under Putin, some of the archives are becoming more secretive again. In part, too, the new focus on Stalin is a result of the flood of Hitler books a few years ago. Two tyrants stood out among all the others in the 20th century, and there was an imbalance in the amount of attention paid to them.

Just as in Hitler's case, though, the primary motivation is fascination with a man and a system so evil that it defies easy explanation. The authors grapple with the core personality of their subject. "His was a complex mind," Robert Service writes in "Stalin: A Biography" (715 pages. Belknap Harvard) , which offers the most detailed account of his life, career and beliefs. "He was not a paranoid schizophrenic. Yet he had the tendencies in the direction of a paranoid and schizophrenic personality disorder." But Rayfield and others point out that Stalin, like Hitler, was accompanied by a huge band of willing--even ghoulishly eager--torturers and executioners. In "The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia" (849 pages. Norton) , Richard Overy examines the parallels and the differences in the two men's lives. As he and several other authors note, their trappings of power--and terror--were strikingly similar. And each was intrigued by the other. "Together with the Germans, we would have been invin-cible," Stalin once wistfully declared.

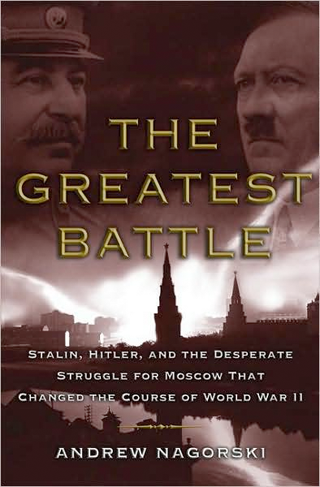

Which leads to the deadly game Stalin and Hitler played during the war--first as allies during the nearly two years of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, then as mortal enemies when Hitler invaded Russia. In "What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa" (310 pages. Yale) , David E. Murphy, a former CIA operative, offers chapter and verse on how Stalin willfully disregarded an avalanche of warnings from his spies that Germany was about to attack. "Stalin's Folly: The Tragic First Ten Days of WWII on the Eastern Front" (326 pages. Houghton Mifflin) by Constantine Pleshakov, the one Russian author in this mix, spells out the disastrous consequences for Soviet forces at the start of the invasion: staggering losses and the collapse of entire military units as the Germans benefited from the element of surprise they never should have had--all brought to life in a colorful narrative full of harrowing individual stories.

Eventually, of course, Stalin and the Red Army recovered and pulled the country back from the brink of defeat. But 27 million Soviet citizens died in the process, many of them needlessly--and some of them at the hands of the machinery of terror that Stalin kept running even as he fought the Germans. As these new books make clear, Stalin wasn't just a monster; he was a disaster for his country and the world.