In the spring of 1951, John Thomas “Jack” Downey was one of about two dozen Yale seniors who gathered in the home of a political-science professor, an aristocratic Swiss émigré, to meet with a recruiter from the recently formed Central Intelligence Agency. The visitor spoke of parachute drops behind enemy lines to organize anticommunist resistance fighters. “It all sounded irresistibly adventurous to young men like us,” Downey recalled.

Having grown up on tales of derring-do by the Office of Strategic Services, the CIA’s World War II predecessor, and faced with the Korean War, Downey and many of his classmates rushed to sign up. They “burned with innocence, patriotism and piety,” Barry Werth writes in “Prisoner of Lies: Jack Downey’s Cold War.” An artfully constructed biography of a young American who ended up in a Chinese prison for 20 years and three months, Mr. Werth’s book is also a vivid chronicle of an era filled with intrigue and with lies that only added to the tragedies of those enmeshed in them.

Downey’s early life looked highly privileged. He was born into an Irish-Catholic clan in Connecticut, which included his uncle Morton Downey, the singer and radio host. At Choate, the all-male prep school, Jack was a star wrestler and excelled academically. He applied to only one college, Yale, since there was no doubt he would be accepted.

None of this came easily. Downey’s father, a respected local judge, died in a car accident when Jack was 8, leaving his mother and her three children with drastically reduced means. Jack picked up a variety of jobs, including caddying and delivering newspapers, and Choate was only possible thanks to a scholarship. He was disciplined, religious—and eager to make the most of every opportunity.

The CIA was fixated on the idea of parachuting exiles into communist countries to organize insurgencies, although its attempts to do so in Albania had already resulted in disaster. In Asia, that meant training former Chinese soldiers for similar missions. As a newly minted CIA officer, a 22-year-old Downey was sent to Japan to support those efforts. In his prison memoir, published posthumously, he admitted that he had doubts about “teaching Chinese soldiers twice my age, asking them to follow our orders to infiltrate their own country.”

Eager for action, he volunteered for a flight out of South Korea to resupply a group of Chinese soldiers recently dropped into Manchuria. Although CIA officers were not supposed to fly over hostile territory, Downey and another junior CIA man, Richard Fecteau, were allowed on board—with strict instructions to deny any affiliation with the agency if they were shot down.

Which was exactly what happened to their C-47 on Nov. 29, 1952. The two pilots were killed, but Downey and Fecteau survived. Their greeting party was well prepared, since the exiles who had been parachuted in earlier had either confessed or were double agents to begin with. “You are Jack,” a Chinese officer told him. Downey stuck with an alias and the flimsy cover story that he was a civilian employee of the Army on a flight that had gone off course, but he had no chance of fooling his captors.

Mr. Werth chillingly portrays the sense of total isolation Downey felt as his interrogators ramped up the pressure for him to come clean. The CIA was convinced that the disappearance of the C-47 meant that all on board had perished. At headquarters, Mr. Werth writes, “regret alternated with relief,” since no one wanted to admit the nature of their mission. Prison guards mercilessly taunted Downey. “We can do whatever we want with you. . . . No one knows you’re alive,” they declared—and they were right.

Kept in shackles, deprived of sleep, minimally fed and increasingly despondent, Downey held out for 16 days before confessing that he worked for the CIA. His spirits revived when he discovered that Fecteau was in a cell nearby, which meant he was not completely alone. Knowing he could no longer lie outright to his captors, he decided to write a “confession” that would “bury them” in meaningless autobiographical details. He produced more than 3,000 pages over eight months.

It was not until two years later that Downey and Fecteau were put on trial. Portrayed as the “chief culprit,” Downey received a life sentence and Fecteau 20 years. China’s public announcement about the trial stunned Washington—and the families of the men, who had been told they were presumed dead.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles protested the verdicts, reviving the cover story that they were civilian employees of the Army who had been lost on a flight from Japan. Mr. Werth persuasively argues that it was the refusal of successive administrations to admit the truth that scuttled hopes for the men’s early release, despite intermittent back-channel negotiations in Warsaw.

But conditions for the captives improved markedly. They were allowed to correspond with their families—and to see them when they visited China. Downey filled his days “with monkish activity,” as Mr. Werth puts it, reading, learning Russian, exercising, and following the much-delayed news and sports he could glean from the magazines he received. He concluded that his fate was “in God’s hands, not my captors’.”

Fecteau was released in 1971, and Downey won his freedom in 1973, after Richard Nixon’s breakthrough visit to China the previous year. The visit included an admission about whom Downey worked for. Downey rebuilt his life with the same quiet determination he demonstrated in prison: He attended Harvard Law School, and followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a judge in Connecticut. He also married a Chinese-American woman.

Even after he learned the extent of his government’s failures to free him, Downey bore no grudges. The CIA awarded him and Fecteau the Distinguished Intelligence Cross in 2013, a year before Downey’s death, at age 84. Mr. Werth’s riveting book is an eloquent tribute to Downey’s steadfast character and courage.

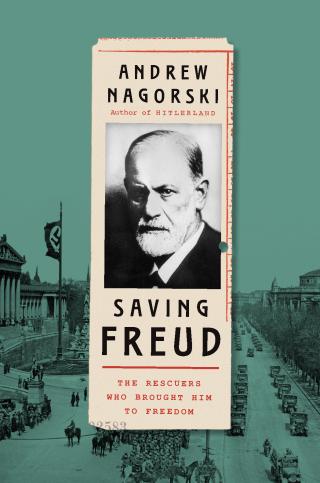

Mr. Nagorski is the author, most recently, of “Saving Freud: The Rescuers Who Brought Him to Freedom.”