By Andrew Nagorski

Of all the Americans who reported from interwar Germany and Central Europe, no one was as well prepared for the assignment as Sigrid Schultz, Berlin bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune. William Shirer, the famed CBS correspondent and author of the monumental The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, was unequivocal in his praise of her skills and the sheer breadth of her knowledge about German society. “No other American correspondent in Berlin knew so much of what was going on behind the scenes as did Sigrid Schultz,” he declared (p. xi).

Today, very few people remember Shultz. As historian Pamela D. Toler points out in her deservedly laudatory, highly engaging biography of the once-famous journalist, this is hardly surprising. “News reporting is an ephemeral art for all but the most notable,” she writes (p. 237). And even in Shultz’s day, when she was churning out stories at an impressive rate from Nazi Germany, which was then the epicenter of the news universe, she was not nearly as well known as Shirer, Dorothy Thompson, who reported for Philadelphia’s Public Ledger and later the New York Evening Post, or Edgar Ansel Mowrer, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Berlin correspondent for the rival Chicago Daily News.

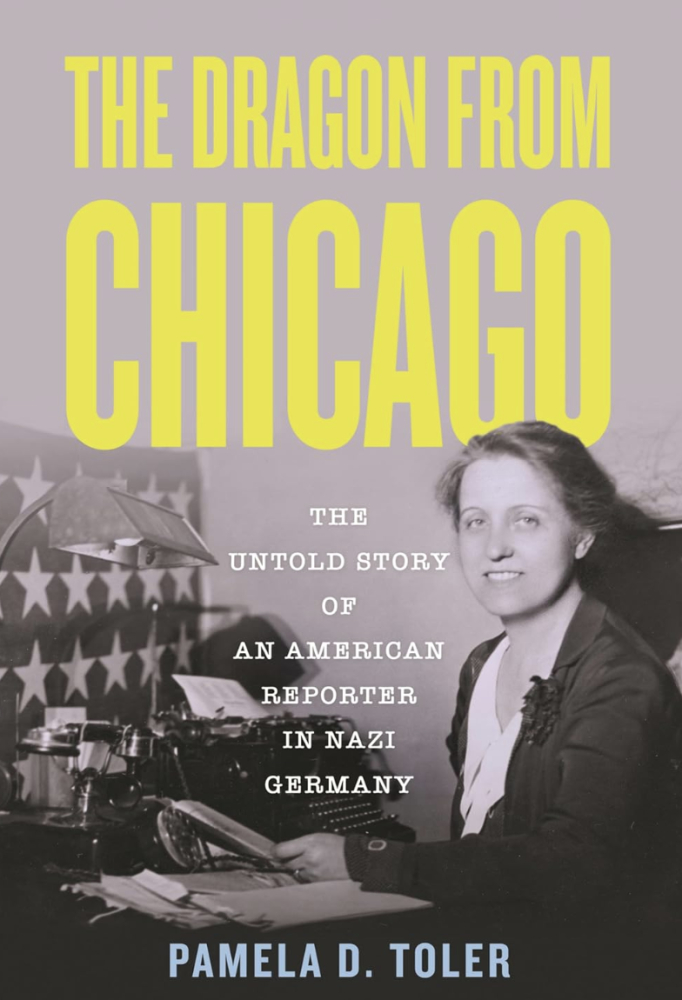

Yet in what could have been a Hollywood scripted moment, Schultz had the audacity to confront Hermann Göring at a Foreign Press Club luncheon after his minions tried to plant compromising materials in her home. Although he claimed she was imagining things, Schultz, whom Toler describes as “small, blonde, and surprisingly formidable” (p. xi), refused to back down—bringing an end to such attempts to entrap her, at least for a while. This prompted the de facto number two Nazi and his staff to call her “that dragon from Chicago” (p. xiv), which serves as the fitting title for Toler’s book.

Schultz clearly touched a nerve—and, more importantly, survived this incident in 1935 to continue reporting from Berlin until 1941, shortly before the United States entered the war, all of which was a testament to her fierce determination to stay on the job no matter how treacherous the conditions.

Who, then, was Sigrid Schultz, and how did she learn to navigate the Berlin—and broader European—landscape? Born in Chicago in 1893, she always clung to her American identity, even though she only spent eight of her early years in the US before her long European sojourn began. Her father was a Norwegian portrait painter, and her mother was born and raised in Wiesbaden, Germany. Schultz said she was not Jewish, but she asserted that her mother had “a ‘cosmopolitan’ background—an interesting word choice given its use as a code word for Jews by the Nazis and later the Soviets,” as Toller puts it (p. 1).

While her father pursued his painting commissions, Sigrid attended schools in France and Germany, with Paris serving as home base for most of the time, and she became fluent in both French and German. She also picked up Norwegian from her father’s relatives and won first-place honors in Italian at her French lycée. On the eve of World War I, the family moved to Berlin. Sigrid took a job teaching English and French in what the owners proudly described as “a finishing school for upper-class young ladies” located in the Harz mountains (p. 12).

Schultz observed the war from what proved to be the losing side. She learned that her fiancé, a Norwegian sailor, had in all probability gone down with his ship, which was torpedoed by a German submarine. Although she subsequently had a couple of romantic relationships, she never married.

When the US entered the conflict in 1917, she was categorized as an enemy alien and stranded in Berlin, where her movements were severely restricted. Nonetheless, she managed to make a living by tutoring wealthy Germans, serving as the sole breadwinner of the family at a time of growing shortages. Her situation improved when Réouf Bey Chadirchi, a visiting Turk who was the mayor of Baghdad and a law professor there, offered her a generous fee to attend classes in international law at the University of Berlin as his proxy, since he did not speak German. She met diplomats, military officers, clerics, and others who visited him, allowing her to develop what would prove to be an astonishing network of sources.

This was perfect training for her next challenge. In the aftermath of Germany’s defeat, Richard Henry Little took charge of the new Berlin bureau of the Chicago Tribune and, impressed by Schultz’s language skills, offered her a job “as a combination interpreter and cub reporter,” as he put it. His additional promise was to make her the “number two man” of his team if she could line up the interviews he wanted (p. 43). She did so and much more, proving to be an invaluable anchor for the newspaper’s entire European operation. By 1925, she took over as its Berlin bureau chief and primary foreign correspondent for Central Europe, with her byline regularly appearing on major stories and scoops.

Schultz did not dwell on the fact that her profession was largely dominated by men or on the obstacles she and other women faced. “She positioned herself as ‘one of the boys,’” Toler notes. In 1969, when the Overseas Press Club honored Schultz with its lifetime achievement award, the inscription declared that “she worked like a newspaperman,” which she accepted as high praise. Unlike the younger women who demanded to be called “newswomen” rather than “newsmen,” she always preferred to be called a “newspaperman” (p. 236).

There was a much more substantive difference of opinion among correspondents in Hitler’s Germany that Toler highlights: the divide between those who were intent on staying put, engaging in whatever amount of self-censorship they felt was needed to avoid expulsion or worse, and those who were prone to test the limits of tolerance of the regime again and again, protecting their sources as much as possible but otherwise seeking to minimize self-censorship.

A personal admission here: As Newsweek’s Moscow bureau chief, I was expelled by the Soviet authorities in 1982, which correctly suggests that my sympathies lie with the latter group mentioned above. When I was researching my book Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power, I came to admire Schultz but less so than Mowrer, her counterpart at the Chicago Daily News. His outspoken anti-Nazi views and courageous reporting so angered the regime that he was driven out of the country less than a year after Hitler took power. The following year, Dorothy Thompson was formally expelled, attracting more headlines.

Even when Schultz returned to the US in early 1941 for what she incorrectly assumed would be only a temporary leave, she was careful in her public statements. She turned down offers to speak to Jewish organizations, fearing that this could provide the Nazis with an excuse to deny her a visa (p. 185). As she had written earlier to Robert McCormick, the publisher of the Chicago Tribune, “I don’t plan to pull an Edgar Mowrer or a Dorothy Thompson and say things that would make it impossible for me to come back” (p. 173).

Schultz’s self-censorship is only one part of her story, and Toller convincingly demonstrates that it would be a mistake to read too much into it. As her confrontation with Göring demonstrated, she certainly did not lack courage—or a willingness to take calculated risks. Her goal was to let readers know the dark truths of the Third Reich by assiduously working her sources while limiting the potential damage to her position.

That meant largely sticking to a just-the-news approach in her bylined articles, which did not prevent her from blunt characterizations. For example, she described the message of the 1936 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg as one of “the fiercest anti-Jewish proclamations yet delivered in the Nazi drive against the Jews.” She knew that Hitler was far from trying to hide that.

However, with her editors’ agreement and complicity, she resorted to a clever subterfuge for publishing stories that could trigger immediate retaliation: using the byline “John Dickson,” a pseudonym that allowed her “to do much of her most important reporting from behind a male mask,” Toler writes (p. 135). Those pieces carried datelines such as Paris and Copenhagen.

Her first such story looked back at the 1934 Night of the Long Knives. “Terror goes with dictatorship as the tide with the ocean,” its lead declared. In an introduction to one of those early articles, the paper claimed that it “had sent one of its trained correspondents into Germany to obtain facts which its accredited correspondents in the Tribune’s Berlin bureau have been unable to cable to America.” Remarkably, the Nazis appeared to be genuinely fooled. It was not until the end of World War II that the paper revealed who really wrote those stories (pp. 133–37).

Once Germany declared war on the United States at the end of 1941, Schultz’s hopes of returning to Berlin were dashed. As the war dominated the news, she was frustrated by the fact that her editors demonstrated declining interest in what she could still recount about Hitler’s early years. She also struggled to drum up interest in a book, finally publishing Germany: Will Try It Again in early 1944. As Toler points out, it was only “a modest success” (p. 200).

Schultz was far better at reporting on the spot than trying her hand at long-form journalism. She demonstrated her fundamental strengths again when she finally returned to Europe in 1945, vividly describing the final push of the war and the gruesome scenes American troops encountered during the liberation of Buchenwald. But here, too, she met with frustration. Pat Maloney, one of her bosses, admitted that her Buchenwald copy was “the most shocking story [he] ever read,” but apologized that the crush of other news meant that he had to cut out two thirds of it (p. 215).

Long before her death at age eighty-seven in 1980, Schultz complained to friends that she was “a has been” (p. 238). That may have been so, but Toler has performed an invaluable service by reminding readers of the accomplishments Schultz achieved during her remarkable career.